Get the Book

Eiffel’s Tower

The story of the world-famous monument and the extraordinary world’s fair that introduced it.

In this first general history of the Eiffel Tower in English, Jill Jonnes—acclaimed author of Conquering Gotham—offers an eye-opening look not only at the construction of one of the modern world’s most iconic structures, but also the epochal event that surrounded its arrival as a wonder of the world. In this marvelously entertaining portrait of Belle Époque France, fear and loathing over Eiffel’s brash design share the spotlight with the celebrities that made the 1889 Exposition Universelle an event to remember—including Buffalo Bill and his sharpshooter Annie Oakley, Thomas Edison, and artists Whistler, Gauguin, and van Gogh. Eiffel’s Tower is a richly textured portrait of an era at the dawn of modernity, reveling in the limitless promise of the future.

Eiffel’s Tower: And the World’s Fair Where Buffalo Bill Beguiled Paris, the Artists Quarreled, and Thomas Edison Became a Count

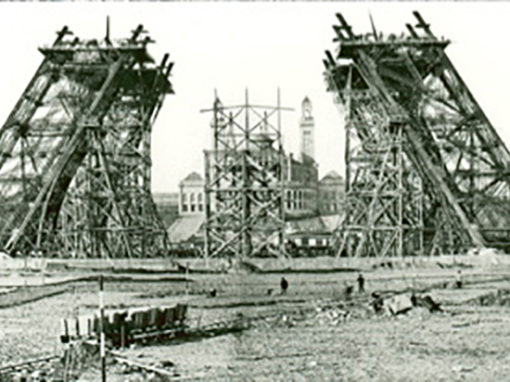

When self-made millionaire and engineer Gustave Eiffel won a contest to erect a colossal tower as the spectacular centerpiece of the 1889 Exposition Universelle, Parisian tastemakers were outraged. They denounced Eiffel’s proposed thousand-foot tower as a “hideous” blot on their historic city, even as fearful residents brought lawsuits amid predictions of certain structural calamity.

Eiffel, a hugely gifted builder of remarkable railroad bridges, persevered, overcoming formidable obstacles. His two hundred workers raced to assemble 18,038 pieces of wrought-iron with two and a half million rivets to create the world’s tallest building. The iron skeleton rose to dominate the Parisian skyline, its sheer size and audacity making the tower a celebrated symbol of technological progress and the modern. In Eiffel’s Tower, Jill Jonnes, author of the critically acclaimed Conquering Gotham, recounts the compelling history of the tower’s conception, building, and reception in Belle Epoque France.

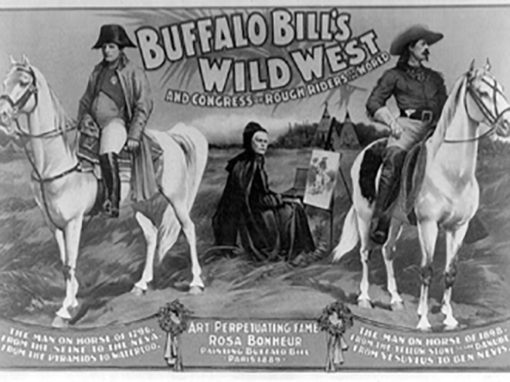

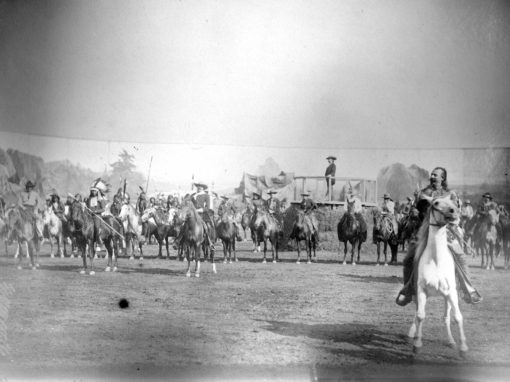

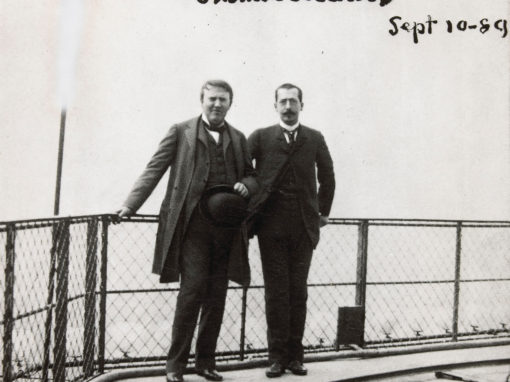

But the Eiffel Tower is only part of this story, for the Paris Exposition itself was a milestone of emerging technology, late 19th century globalism, and an extraordinary flourishing of the arts and journalism. Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, featuring famous sharpshooter Annie Oakley and a full retinue of Native Americans, enthralled Parisians, while Thomas Edison, come to promote his new talking phonograph in Europe, was feted as a genius; the painters Whistler, Gauguin, and van Gogh were exploring new frontiers in art, and James Gordon Bennett, Jr. of the Paris Herald was reinventing the news. At the fanciful exposition grounds, fairgoers crowded Asian and African shops and mock villages, fascinated by these first glimpses the newly global world of colonial empire and trade.

Eiffel’s Tower is a richly textured portrait of a visionary, of an architectural icon that became the glamorous symbol of Paris and French culture, and of an era at the dawn of modernity, reveling in the limitless promise of the future.

NBC Nightly News Films

The 135th Anniversary of an Icon: The Eiffel Tower

September 12, 2024

Jill shares her insights about Gustave Eiffel and his tower in this two-part NBC Nightly News film.

With the recent conclusion of the Olympic Games in Paris, a debate whether the rings should stay on the Eiffel Tower is now underway. Originally constructed for the 1889 Exposition Universelle, a look back at the history behind this iconic landmark, its impact on the global stage, tourism, and role in popular culture.

“Ms. Jonnes does a fine job of walking us through the fair, where visitors were immersed in a typical late-nineteenth-century stew of high-minded educational exhibits and cheap thrills.”

“In splendid detail, Jonnes examines the importance of the tower in its own historical moment.”

“This panorama of life near the end of the nineteenth century is vivid, detailed and engrossing. …A well-researched read that will transport them back to a time as complex and crazy as our own.”

Gallery

Get the Book

Notes

A few years ago, while traveling in Italy, I was reading Ross King’s Michelangelo and the Pope’s Ceiling about the artist’s four-year struggle to paint 12,000-square-feet of frescos high on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. “What fun,” I thought as the painter had yet another falling out with his papal patron, “to write a book about such a famous man and his monument.” I had also enjoyed King’s earlier book, Brunelleschi’s Dome, the story of secretive clockmaker Felippo Brunelleschi and how he solved the problem of constructing the great dome on the Sante Maria del Fiore Cathedral in 15th-century Florence.

I, too, wanted to write about a celebrated building. When I cast my eye about, I discovered that no full-scale history had been written in more than thirty years about that most famous of all monuments—Gustave Eiffel’s Tower. I first visited the Eiffel Tower as a girl of seven. It remains a vivid memory to this day—the sensation of walking down from the second platform on that summer day, round and round and round, feeling slightly giddy on those seemingly endless wrought-iron steps, the Paris cityscape revolving around as I descended, a small person on a gigantic structure.

In 1960, my family moved to Paris for several years, and the Eiffel Tower faded into an everyday sight. Only decades later, when I had not been in Paris for a long time did I again experience the tower’s mystique. On a cold clear winter night, my husband and I had joined his scientist colleagues up in one of the tower’s restaurants. As we ate a dinner of many courses—I still remember a delectable dark chocolate gateau—the lights of Paris sparkled brilliantly below. It felt very glamorous.

As soon as I began my research, I was reminded that the Eiffel Tower had been the centerpiece of the 1889 Paris World’s Fair. And what a cast of marvelous Belle Epoque and Gilded Age characters vied for attention there: Gustave Eiffel, Buffalo Bill, Annie Oakley, the van Gogh brothers, Paul Gauguin, Thomas Edison, James McNeil Whistler, Rosa Bonheur, James Gordon Bennett Jr., and Whitelaw Reid. Woven all through the fair was an amusing French-American rivalry/friendship that felt completely contemporary.

My first research stop was Cody, Wyoming, a small town founded by Buffalo Bill and home to the world class Buffalo Bill Historical Center and its McCracken Research Library. The Wild West show and Annie Oakley both kept Paris scrapbooks that were filled with detailed articles from the French and American press about their triumphant Paris season. Guillaume Bufle! Mademoiselle Oakley! Here was the beginning of the French love affair with the American West. Like everyone else who ever spent time with Cody or Annie, I came away smitten with their talent and charm. And there was something endlessly amusing about reading about them in French.

When Joseph Harriss, a longtime American journalist based in Paris, had worked on The Tallest Tower in the 1970s, the Eiffel family still controlled Gustave Eiffel’s papers. In 1981, they had donated that archive to the Musee d’Orsay. And so, the winter of 2006 found me happily ensconced in the museum’s library overlooking the Seine. There on an overcast day, I read one of the five copies of Eiffel’s typed memoir and numerous hand-written letters. On subsequent visits, I studied his leather-bound Livre d’or with its signatures of famous visitors to the tower that inaugural year, examined the stacks of old photos, and wished I had been present at some of the dinners whose charming illustrated menus Eiffel kept as souvenirs. Knowing how thoroughly Eiffel would be tarnished by the Panama Canal scandal, many of the documents seemed poignant, written as they were when he was literally at the top of the world with no inkling of the scandal that would engulf him. There were, of course, later papers written very much with an eye to burnishing his image.

At the starkly modern Bibliotheque Nationale, after some trouble, I located the whole run of Le Figaro de la Tour—a Eureka! moment, for this was the daily paper published during the fair on the tower’s second floor. It was a never-plumbed treasure-trove of stories about daily life on the Eiffel Tower—visits from the Wild West Indians, the Shah of Persia, and other 19th-century luminaries, as well as little vignettes of the lark who built a nest high upon the tower or a shepherd from Landes on wooden stilts who ascended the stairs to the second platform.

The new cornucopia of on-line materials have also transformed historical research. With the ever-growing historical newspaper and periodical databases, I could sit at a computer and type in, for instance, Otis and Eiffel, and summon up articles heretofore buried away that revealed numerous lawsuits. Thanks to the Internet and enterprising scholars and corporations, I could unearth in the virtual world wonderful facts and details earlier writers could only dream of.

I already knew from working on Empires of Light: Edison, Tesla, Westinghouse and the Race to Electrify the World (2003) that the most important Thomas Edison papers were available on an amazing website. Once again, I trolled that and marveled as hand-written letters appeared on my screen providing scathing particulars of Edison’s unhappiness with his British partner Colonel Gouraud, as well as details of his triumphant visit to Paris in late summer of 1889. In the same way, since 2003, the University of Glasgow has put large numbers of James McNeil Whistler’s correspondence on line. Again, through these letters and notes I could track Whistler’s tarrying in London, his feuds, and his anguish at his wife’s death. I can only thank those who create these invaluable research troves.

And yet, as much as one can track down elusive facts these days, there still remain unanswered little mysteries. I knew Buffalo Bill had ascended the Eiffel Tower because I saw his signature in Eiffel’s Livre d’or, but I would have liked to know what month or day. Cody had not bothered to date his autograph. I read in one old biography that Cody ascended on August 10, but Le Figaro de la Tour, which tracked even minor celebrities who ascended, had no report. And then, did Gustave Eiffel ever reciprocate Cody’s visit and attend the Wild West show, which was the fashionable thing to do? Again, I could find no mention in the usual places.

A final frustration was not fully knowing the whereabouts and activities of the incomparably eccentric James Gordon Bennett Jr., millionaire publisher of the Paris Herald. Bennett had been part of a hunting party led by Buffalo Bill in 1871 and a great promoter over the years of Cody’s career. Surely Bennett and Cody must have met up sometime that summer in Paris. They were both world-class carousers, and one yearned for some hint of a reunion. But Bennett had a policy of never allowing his own name in his newspaper.

Then I learned that Buffalo Bill had kept a personal scrapbook of his half year in Paris. Surely, it would hold the answers to these lingering questions. With the help of Paul Fees, Cody expert, I talked to the book’s owner, Michael del Castello, who kindly lent it to me. Imagine my excitement as I began to turn its heavy yellowing pages, hopeful that I might find among the personal notes and invitations something from Eiffel or Bennett that would clear up these small but nonetheless unanswered questions. When I turned a page and realized the notes and invitations were now in Italian—these were pages devoted to the Italian part of his European tour, I had to sadly acknowledge defeat. My only consolation was finding Cody’s invitation to Edison’s gala at Le Figaro’scharming offices and a hand-written note to Cody from the artist Rosa Bonheur on the subject of her mustangs.

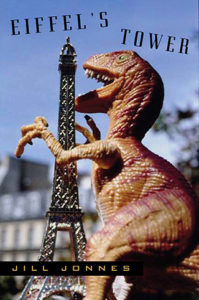

Of course, eventually, the manuscript is due and the book enters production, which entails editing, copy editing, proof-reading, i.e. rigorous examination of your sentences, paragraphs, facts, and photographs. Amidst all the ensuing revisions, corrections etc., I received a wonderful e-mail. My book cover! Rarely does the author have any say on the cover, and it can be quite a surprise—pleasant or otherwise. With Eiffel’s Tower, I was sent two purported choices—both wonderful. The gorgeous cover that came to grace the actual book and then this hilarious “Godzilla Attacks the Tower” staged by a playful art director. As they say on-line, LOL! I hope to promote a few chuckles here by sharing it.

Working on the story of the Eiffel Tower and the Exposition Universelle has been a delight. I felt so charmed by my ten characters and loved following their triumphs and travails. For quite a few, the 1889 World’s Fair was the pinnacle of their careers. I also came away feeling that the fair had a greater meaning than mere amusement, for it really presaged the global world we inhabit today.